About the Author: Dr. Alexander Mazzaferro, SIFK Postdoctoral Researcher and Instructor, is a scholar of early American literature working at the intersection of the history of science and the history of political thought. He is currently teaching a graduate course, Political Theologies of Slavery and Freedom in the Atlantic World, which explores the role that Christian and non-Christian theologies played in the rise and contestation of Atlantic slavery. Learn more about his courses and research here.

The Covid-19 pandemic’s racial disparities are by now common knowledge.

The novel coronavirus is killing black Americans at disproportionately higher rates than other ethnicities.1 Citing a study conducted by the American Public Media Research Lab,2 CNN reports that while African Americans account for around 13% of the U.S. population, they make up 27% of Covid-19 deaths. White Americans, by contrast, account for 60% of the population but make up 49% of Covid-19 deaths.3 According to The New York Times, “African-Americans account for more than half of those who have tested positive and 72 percent of virus-related fatalities in Chicago, even though they make up a little less than a third of the population.” And this staggering trend has proved typical of other U.S. cities.4

Latino communities are also experiencing alarmingly high rates of infection and mortality,5 as are Native Americans.6 And these disparities are not exclusive to the U.S., as reports of disproportionate impacts on African and South Asian communities in Britain demonstrate.7 Moreover, nonwhites are also experiencing job loss at higher rates than white Americans,8 and this has only reinforced the economic disparities that made them more vulnerable to the virus in the first place.

What initially seemed an equal opportunity killer has thus become a magnifier of inequalities that predate it by centuries. And this has led commentators to argue that blackness itself has become a “preexisting condition”9 and to frame the pandemic as nothing less than a civil rights issue.10

In a similar spirit, I want to take a long view of the Covid-19 outbreak, positioning it as the latest installment in a deep history of racially maldistributed mortality traceable to colonialism, slavery, and their legacies. Despite the massive social shifts that distinguish contemporary America from its distant past, there are significant continuities linking the racialized health disparities of the seventeenth and eighteenth centuries and those of today. Revisiting the response to earlier outbreaks thus provides an opportunity to reflect on the mechanisms that allowed nonwhite mass death to be normalized as a routine part of early modern life. With the rise of providentialism—a way of reading earthly events as divinely orchestrated—insidious new forms of passivity became available to Europeans who otherwise prided themselves on their ability to change the world.

Providentialism and Passivity

Published in 1588, Thomas Hariot’s A Briefe and True Report of the New Found Land of Virginia recounts the expedition sent to colonize Roanoke Island and its environs in 1585. The text’s best-known passage describes the devastating effect that European diseases had on local tribes like the Secotans. Hariot explains that whenever the explorers left a native affront “unpunished,” the inhabitants of the village where it occurred “began to die very fast.” When this epidemic baffles tribal elders (“they neither knew what it was, nor how to cure it”) they turn to what we would now call supernatural explanations.11

In Hariot’s telling, the Secotans “were perswaded that it [the epidemic] was the worke of our God through our meanes, and that wee by him might kil … whom[ever] wee” wanted “by shooting invisible bullets into them.” As a result, he claims, “some people could not tel whether to think us gods or men.” Hariot’s indigenous ventriloquism leaves open the possibility that these were not in fact the Secotans’ opinions; but even as he gains some distance from them, he also concedes that the explorers fundamentally share them: “wee our selves … thinke no lesse.”12 Writing long before the advent of modern germ theory, he could not resist reading Native Americans’ and Europeans’ disparate immunities providentially, as evidence of a hierarchy that is not just physical but metaphysical.

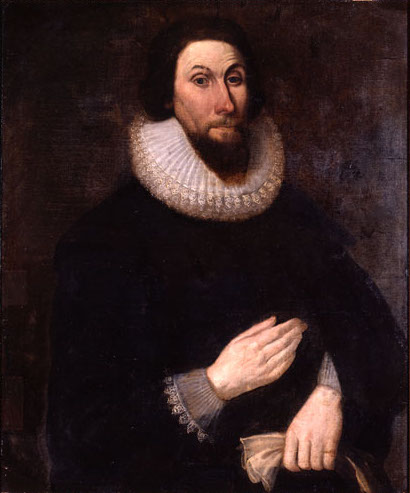

In 1629, Massachusetts Bay Governor John Winthrop similarly insisted that “God hath consumed the natives [of New England] with a miraculous plague” to make room for puritan settlers.13 Winthrop’s comfortable sense that indigenous mass death was part of God’s plan reflects his investment in the same interpretative mode we saw in Hariot: providentialism. Despite his use of the term “miraculous,” which might imply a break with the laws of nature, Winthrop’s account displays the hallmark of providential interpretation: the assumption that God accomplishes his purposes on earth using natural “meanes.” In a providentialist scheme, the fact that someone survived or succumbed to a shipwreck, blizzard, battle, or “plague” acquired immense spiritual meaning. But because they remained grounded in the laws of nature, such spectacular events could also begin to seem ordinary—and thus unavoidable.

God’s providential role in orchestrating indigenous mass death simultaneously empowered Euro-Christians and freed them from any obligation to intervene. Ministering medically to sick Secotans, for example, would have constituted an empowering performance of ethnocentric superiority in its own right.14 But this was not the explorers’ response. Instead, the providential readings that Hariot and Winthrop offer render Native American epidemics a fact of New World life requiring no human intervention, even though they are entirely unprecedented and just began when the Europeans arrived.

The utility of providentialism lay, then, in its flexible coding of human agency: it allowed writers to justify activity on one front as the earthly “meanes” of realizing God’s will, while justifying passivity on another front in order to avoid impeding that will. In a study that takes its title from Winthrop’s “miraculous plague” remark, Cristobal Silva uses these and other episodes from colonial medical history to demonstrate “the power of epidemiology to naturalize political and economic disparities.”15 Drawing a parallel to today, we might say of these early American outbreaks what Kimberlé Williams Crenshaw has said about the racially stratified response to Covid-19: both events lay bare unspoken assumptions about “whose vulnerability warrants robust interventions and whose does not.”16

Plantation Slavery and the Cosmic Status Quo

It is tempting to imagine that, as mainstream western culture became more secular, providential fantasies of European supremacy became less tenable. But historians have taught us that modernity is not only rife with racial violence but also less secular than we might think. As scholars like Colin Kidd, Katherine Gerbner, and J. Kameron Carter observe, racial ideology was originally grounded in Christian theology and continues to draw on its repertoire of transcendence even without explicitly endorsing it.17

Rejecting Eurocentric narratives of secularization, Jared Hickman argues that the “discovery” of the Americas in 1492 encouraged the conflation of communities with the gods they worshipped and thereby lent earthly confrontations cosmological significance. As racial hierarchies became the keynote of the modern world, their beneficiaries normalized them as the “cosmic status quo.” As a result, “Euro-Christians are placed in a position to function as rather than to have to reject … God.”18 This explains the slippage in Hariot’s Report between the idea that the epidemic is “the worke of our God through our meanes” and the notion that Euro-Christians themselves are “gods” rather than “men.”19 It also explains why resistance to colonialism, slavery, and racism has so often been waged in theological terms.

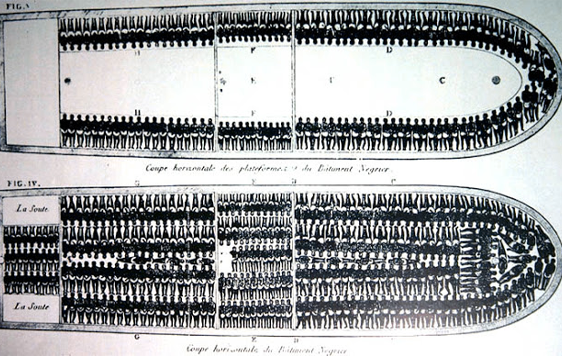

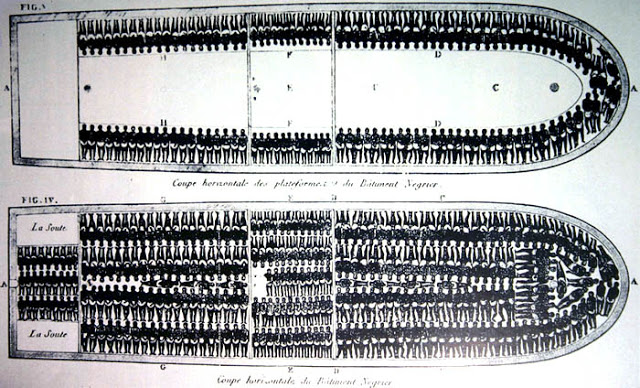

The process of western self-deification is apparent in the archives of New World slavery as well as native genocide, and here too racialized mortality rates played a crucial role. An extravagant death toll attended every step of the Atlantic slave trade: from capture in Africa and the harrowing Middle Passage to the plantation Americas, where malnutrition, overwork, suicide, and disease killed as many as half of all Africans imported to the British Caribbean within three years of their arrival.20 Thus the ex-slave and antislavery author Olaudah Equiano thought it “no wonder that the decrease should require 20,000 new negroes annually to fill up the vacant places of the dead.”21 And thus the historian Vincent Brown has deemed plantation societies like eighteenth-century Jamaica a “demographic catastrophe.”22

At the same time that British slavery entrenched itself, providentialism experienced a shift. Where Hariot and Winthrop had treated specific events as divine interventions, the Enlightenment inspired other writers to imagine a more hands-off God, who set major systems like “the Market” in motion and then accomplished his purposes simply by allowing them to run themselves. Nonetheless, this refurbished providentialism proved as adept as its predecessor at rendering slavery’s exorbitant mortality rates a routine part of the “cosmic status quo.” Caitlin Rosenthal notes that plantation accounting practices framed black mass death not as human loss but as “diminished inventory.”23 But far from being secular, this coldly calculating view reflected the persistent belief that racial hierarchy was divinely sanctioned. As a functioning global capitalist economy came to seem like the highest good God had designed for “humanity,” the racial maldistribution of mortality was rationalized as so much collateral damage.24

Writing as the sugar industry was making slavery a fact of life in 1650s Barbados, Richard Ligon insisted that Africans “set no great value upon their lives” and focused his energies on maximizing their spiritual, rather than earthly, prospects by pressing for their long-denied Christian conversion.25 A century later, the physician and poet James Grainger’s Essay on the More Common West-India Diseases (1764) warned in apocalyptic tones that “masters … must answer before the Almighty for their conduct toward their Negroes.” But rather than propose emancipation, the text demanded that planters provide their slaves with better medical care. Grainger lamented that “hundreds of these useful people are yearly sacrificed” to preventable or treatable illness, but he found it no contradiction to do so in the name of “profit” as well as “humanity.” Fine-tuning, in short, was welcome, but the system itself seemed fundamentally sound.26

Conclusion

By 1829, the providential interpretation of the slave system was so prevalent that the Christian abolitionist David Walker had even heard fellow African Americans say “there is no use in trying to better our condition."27 He thus set out to correct this fatalism. In so doing, his controversial Appeal to the Coloured Citizens of the World modeled the kind of imaginative response that today’s pandemic demands.

As President Barack Obama observed in the virtual commencement address he recently delivered to 2020 graduates of America’s Historically Black Colleges and Universities: the Covid-19 outbreak not only “spotlights the underlying inequalities and extra burdens that black communities have historically had to deal with in this country,” it also clarifies that today’s “status quo needs fixing.”28 The pandemic has both fed on and exacerbated vestiges of slavery like ghettoization, poverty, underemployment, mass incarceration, a failed healthcare system, and lower life expectancy.29 But it also provides an opportunity to reject them as the Normal to which we might return.

If providentialism is no longer our primary mode of interpretation today, the risk of normalizing racially maldistributed mortality rates remains. Viewing the Covid-19 pandemic through the lens of past outbreaks counteracts that risk by foregrounding the revisability of what counts as ordinary. Taking a historically long view of the present crisis positions nonwhite suffering not as a foregone conclusion to be met with passivity but as an aberration requiring intervention.30 In other words, rendering racialized health disparities common knowledge promises to help prevent them from becoming commonplace.

Cite this Article:

"Mazzaferro, Alexander. 2020. Covid-19 and the Long History of Racially Maldistributed Mortality, May 26, 2020. Formations, The University of Chicago. https://sifk.uchicago.edu/blogs/article/covid-19-and-the-long-history-of-racially-maldistributed-mortality/."

Notes:

1 According to the Centers for Disease Control and Prevention, “current data suggest a disproportionate burden of illness and death among racial and ethnic minority groups.” See “COVID-19 in Racial and Ethnic Minority Groups,” CDC.gov, April 22 2020, https://www.cdc.gov/coronavirus/2019-ncov/need-extra-precautions/racial-ethnic-minorities.html.

2 “The Color of Coronavirus: Covid-19 Deaths by Race and Ethnicity in the U.S.,” American Public Media Research Lab, May 12 2020, https://www.apmresearchlab.org/covid/deaths-by-race.

3 Harmeet Kaur, “The coronavirus pandemic is hitting black and brown Americans especially hard on all fronts,” CNN, May 8 2020, https://www.cnn.com/2020/05/08/us/coronavirus-pandemic-race-impact-trnd/index.html. See also Reis Thebault, Andrew Ba Tran, and Vanessa Williams, “The coronavirus is infecting and killing black Americans at an alarmingly high rate,” The Washington Post, April 7 2020, https://www.washingtonpost.com/nation/2020/04/07/coronavirus-is-infecting-killing-black-americans-an-alarmingly-high-rate-post-analysis-shows.

4 John Eligon, Audra D. S. Burch, Dionne Searcey and Richard A. Oppel Jr., “Black Americans Face Alarming Rates of Coronavirus Infection in Some States,” The New York Times, April 7 2020, https://www.nytimes.com/2020/04/07/us/coronavirus-race.html.

5 Miriam Jordan and Richard A. Oppel Jr., “For Latinos and Covid-19, Doctors Are Seeing an ‘Alarming’ Disparity,” The New York Times, May 7 2020, https://www.nytimes.com/2020/05/07/us/coronavirus-latinos-disparity.html.

6 Serena Gordon, “Why Are Blacks, Other Minorities Hardest Hit By COVID-19?,” U.S. News & World Report, May 6 2020, https://www.usnews.com/news/health-news/articles/2020-05-06/why-are-blacks-other-minorities-hardest-hit-by-covid-19.

7 Benjamin Mueller, “Coronavirus Killing Black Britons at Twice the Rate of Whites,” The New York Times, May 7 2020, https://www.nytimes.com/2020/05/07/world/europe/coronavirus-uk-black-britons.html.

8 Jacqueline Alemany with Brent D. Griffiths, “Power Up: Black and Hispanic Americans are getting laid off at higher rates than white workers,” The Washington Post, May 7 2020, https://www.washingtonpost.com/news/powerpost/paloma/powerup/2020/05/07/powerup-black-and-hispanic-americans-are-getting-laid-off-at-higher-rates-than-white-workers/5eb38eb688e0fa17cddf4497/.

9 Kimberlé Williams Crenshaw, “When Blackness Is a Preexisting Condition: How modern disaster relief has hurt African American communities,” The New Republic, May 4 2020, https://newrepublic.com/article/157537/blackness-preexisting-condition-coronavirus-katrina-disaster-relief.

10 Audra D. S. Burch, “Why the Virus Is a Civil Rights Issue: ‘The Pain Will Not Be Shared Equally,’” The New York Times, April 19 2020, https://www.nytimes.com/2020/04/19/us/coronavirus-civil-rights.html.

11 Thomas Hariot, A Briefe and True Report of the New Found Land of Virginia, in Captain John Smith, Writings with Other Narratives of Roanoke, Jamestown, and the First English Settlement of America, ed. James Horn (New York: Library of America, 2007), 900.

12 Hariot, A Briefe and True Report, in Smith, Writings, 901, 902, 901, 902.

13 John Winthrop, Generall Considerations for the Plantation in New England (1629), quoted in Cristobal Silva, Miraculous Plagues: An Epidemiology of Early New England Narrative (New York: Oxford University Press, 2011), 17. Silva notes that, between 1616 and 1619, these epidemics killed “95 percent of the indigenous population” of New England (17).

14 Kelly Wisecup describes such a response in Medical Encounters: Knowledge and Identity in Early American Literatures (Amherst: University of Massachusetts Press, 2013), Chapter 2.

15 Silva, Miraculous Plagues, 50.

16 Crenshaw, “When Blackness Is a Preexisting Condition,” The New Republic, May 4 2020, https://newrepublic.com/article/157537/blackness-preexisting-condition-coronavirus-katrina-disaster-relief.

17 See Colin Kidd, The Forging of Races: Race and Scripture in the Protestant Atlantic World, 1600–2000 (Cambridge: Cambridge University Press, 2006); Katherine Gerbner, Christian Slavery: Conversion and Race in the Protestant Atlantic World (Philadelphia: University of Pennsylvania Press, 2018); and J. Kameron Carter, Race: A Theological Account (New York: Oxford University Press, 2008).

18 Jared Hickman, Black Prometheus: Race and Radicalism in the Age of Atlantic Slavery (New York: Oxford University Press, 2016), 52, 60 (emphasis added).

19 Hariot, A Briefe and True Report, in Smith, Writings, 901.

20 Caitlin Rosenthal, Accounting for Slavery: Masters and Management (Cambridge: Harvard University Press, 2018), 12.

21 Olaudah Equiano, The Interesting Narrative of the Life of Olaudah Equiano, in Unchained Voices: An Anthology of Black Authors in the English-Speaking World of the Eighteenth Century, ed. Vincent Carretta (1789; Lexington: University Press of Kentucky, 2003), 223.

22 Vincent Brown, The Reaper’s Garden: Death and Power in the World of Atlantic Slavery (Cambridge: Harvard University Press, 2008), 20.

23 Rosenthal, Accounting for Slavery, 12.

24 On this “providential Deist” view of the global capitalist economy, see Charles Taylor, A Secular Age (Cambridge: Belknap Press for Harvard University Press, 2007), Chapter 6, esp. 229-30.

25 Richard Ligon, A True and Exact History of the Island of Barbados, ed. Karen Ordahl Kupperman (1657; Indianapolis: Hackett, 2011), 106.

26 James Grainger, An Essay on the More Common West-India Diseases (London, 1764), 88, i, iii, 89.

27 David Walker, Walker’s Appeal, in Four Articles: Together with a Preamble, to the Coloured Citizens of the World, But in Particular, and Very Expressly, to Those of the United States of America (Boston: 1829), 4.

28 See “Read: Obama delivers H.B.C.U. Commencement Speech,” Axios, May 17 2020, https://www.axios.com/read-obama-delivers-hbcu-commencement-speech-ab461eec-7ee4-42ff-ad52-a7373afaa4f1.html.

29 According to CNN, African Americans “are almost twice as likely as white residents to be uninsured” and “black workers are less likely than their white and Asian counterparts to be employed in jobs that allow work from home, reducing risk of exposure to the virus.” Likewise, The New York Times reports that African Americans are “more likely to have existing health conditions and face racial bias that prevents them from getting proper treatment.” See Fredreka Schouten, “The people in power don’t look like the people hit hardest by Covid-19,” CNN, May 8 2020, https://www.cnn.com/2020/05/06/politics/black-leaders-confront-covid-19/index.html; and Eligon, et al., “Black Americans Face Alarming Rates of Coronavirus Infection,” The New York Times, April 7 2020, https://www.nytimes.com/2020/04/07/us/coronavirus-race.html. See also the Chicago Tribune’s reporting on the 2019 study that found that residents of Chicago’s predominantly white Streeterville neighborhood lived 30 years longer on average than residents of Chicago’s predominantly black Englewood neighborhood—the largest such discrepancy in the country: Lisa Schencker, “Chicago’s lifespan gap,” Chicago Tribune, June 6 2019, https://www.chicagotribune.com/business/ct-biz-chicago-has-largest-life-expectancy-gap-between-neighborhoods-20190605-story.html.

30 For a related argument, see SIFK postdoctoral fellow Dr. Yan Slobodkin’s recent essays on the normalization of suffering and the limits of empathy: Yan Slobodkin, “Famine Is a Choice,” Slate, May 11 2020, https://slate.com/news-and-politics/2020/05/famine-is-a-choice.html; and Yan Slobodkin, “The Limits of Empathy,” Formations, April 20 2020, https://sifk.uchicago.edu/news/the-limits-of-empathy.

“Indian Conjuror” depicted in Hariot’s Report.

Portrait of John Winthrop.

Slave ship diagram (1788).

Olaudah Equiano’s author portrait.

Title page of Walker’s Appeal.